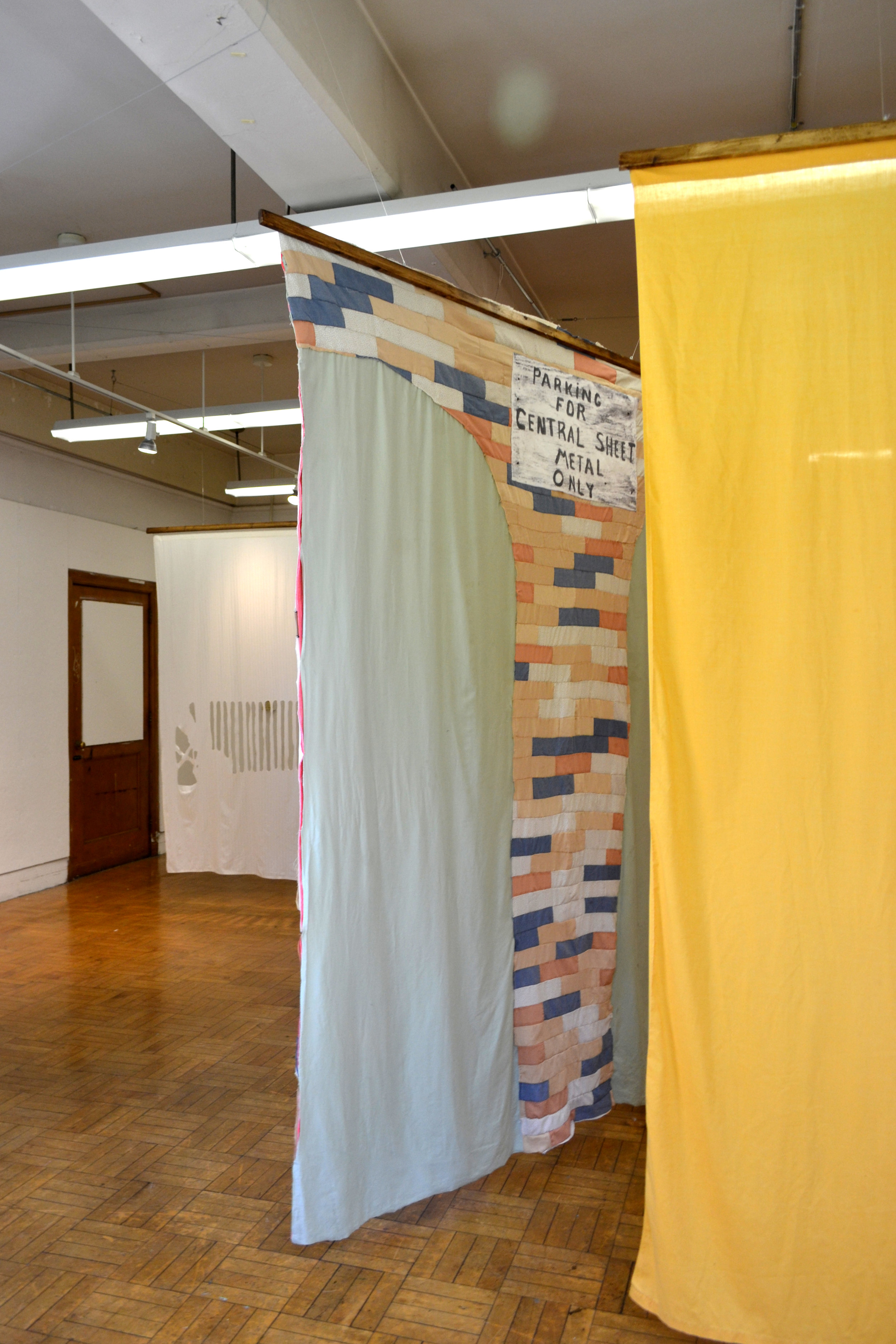

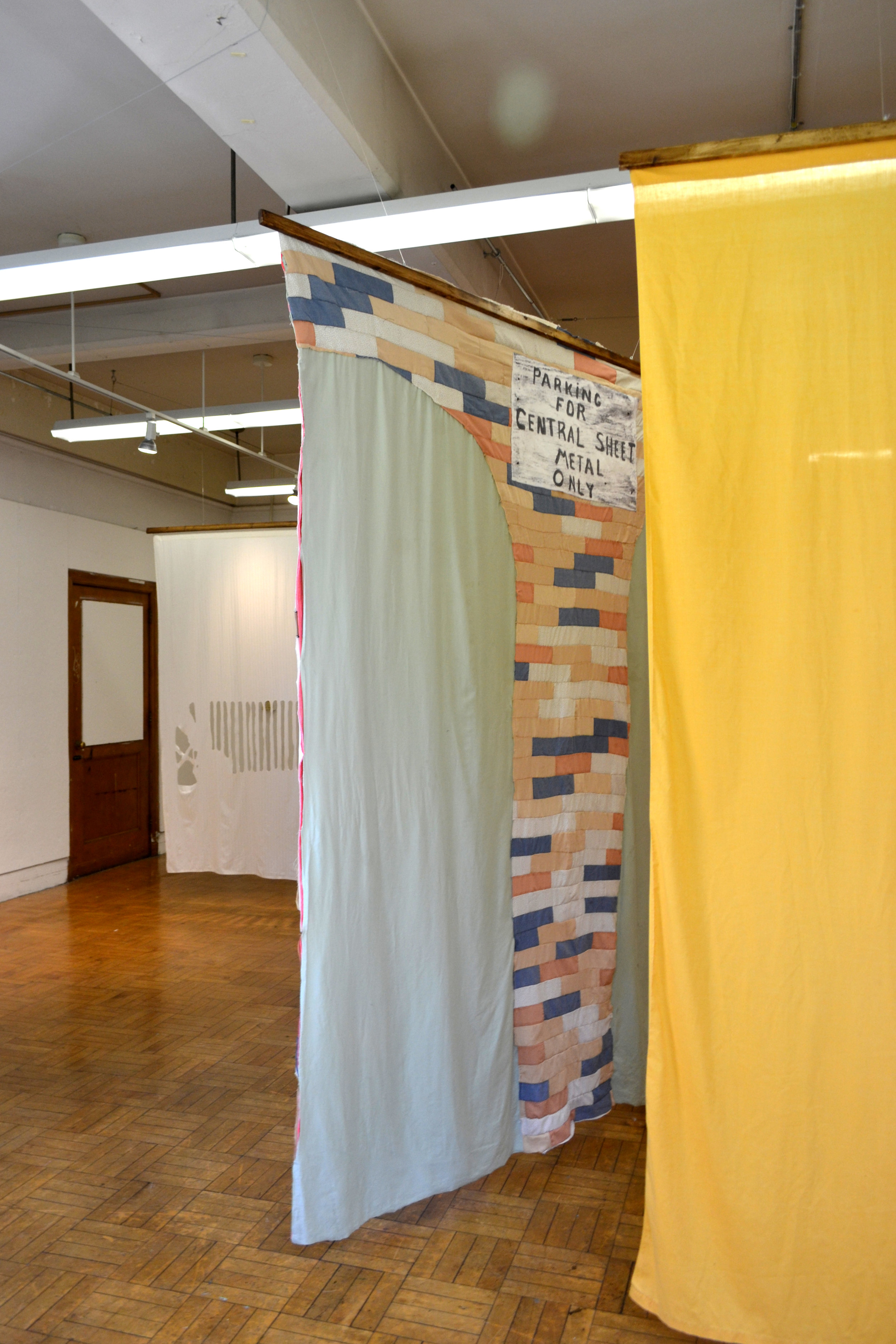

Mixed Media Installation (Hand/Machine Quilting, Digitally Printed Fabric, Hand/Digital Embroidery); three double-faced quilts and six hanging pieces acting as apertures through which to view the quilts, 2018.

The first several times my dad drove me down the street in Providence that he grew up on, I could never remember which house was his (151, 6th Street). I could remember the cemetery where he fell out of a tree as a child (Swan Point) and which high school he went to (Hope) and even which delicatessen he worked in as a teenager (Miller’s). However, the unassuming exterior of the green house just did not stick with me. I have since realized that my inability to recognize my father’s house was due to the private, intimate nature of narratives contained in home spaces, and how they are often masked by the anonymity of the house’s facade. After years of experiencing the same locations, I have found it impossible to remember my own experiences without superimposing the memories of my father’s adolescence on top of my own. Through my work, I have chosen to illustrate the ever-present role of soft goods within the home in relation to the intersection of object, memory, and narrative and of inheriting a city as one might inherit the furniture of their relatives. In the same way that internet commentary, captions on family photos or highlighter streaks across the pages of printed work act as a layer of context atop methods of general communications, textiles perform the act of annotating a space and claiming ownership over the experience of that space whether on the body or in the home.

The importance of annotations are evident through the necessity of the context they often provide (in the case of old photography and the like) as they are the link that enable the viewer to establish an emotional connection with the imagery. By treating quilting as the exploration of a personal narrative, the lived-in quality of the materials are the evidence of having existed in these locations. As much as my work resides in a space informed by living in both the North and Southeastern United States, it is in dialogue with this deeply rooted American tradition that exists with the tension of both archival dissection and contemporary sensibility. Through examining objects that act as vehicles for memory and sentiment, I have noticed this relationship is more nuanced as location becomes relative and objects take on the role of place holders for past experiences. In my work, I explore the limitations of narrative as they are defined through their ability to reconcile text with the relationship between the viewer and the physicality of objects that are communicating these histories.

As family heirlooms are packed into trunks and moved to new locations, they begin to simultaneously operate in both locational narratives, amongst those who both own the items and feel emotional claim (or connection) to them. This method of describing yourself through these objects and their histories is at the core of my work, and of my Degree Project.

Mixed Media Installation (Hand/Machine Quilting, Digitally Printed Fabric, Hand/Digital Embroidery); three double-faced quilts and six hanging pieces acting as apertures through which to view the quilts, 2018.

The first several times my dad drove me down the street in Providence that he grew up on, I could never remember which house was his (151, 6th Street). I could remember the cemetery where he fell out of a tree as a child (Swan Point) and which high school he went to (Hope) and even which delicatessen he worked in as a teenager (Miller’s). However, the unassuming exterior of the green house just did not stick with me. I have since realized that my inability to recognize my father’s house was due to the private, intimate nature of narratives contained in home spaces, and how they are often masked by the anonymity of the house’s facade. After years of experiencing the same locations, I have found it impossible to remember my own experiences without superimposing the memories of my father’s adolescence on top of my own. Through my work, I have chosen to illustrate the ever-present role of soft goods within the home in relation to the intersection of object, memory, and narrative and of inheriting a city as one might inherit the furniture of their relatives. In the same way that internet commentary, captions on family photos or highlighter streaks across the pages of printed work act as a layer of context atop methods of general communications, textiles perform the act of annotating a space and claiming ownership over the experience of that space whether on the body or in the home.

The importance of annotations are evident through the necessity of the context they often provide (in the case of old photography and the like) as they are the link that enable the viewer to establish an emotional connection with the imagery. By treating quilting as the exploration of a personal narrative, the lived-in quality of the materials are the evidence of having existed in these locations. As much as my work resides in a space informed by living in both the North and Southeastern United States, it is in dialogue with this deeply rooted American tradition that exists with the tension of both archival dissection and contemporary sensibility. Through examining objects that act as vehicles for memory and sentiment, I have noticed this relationship is more nuanced as location becomes relative and objects take on the role of place holders for past experiences. In my work, I explore the limitations of narrative as they are defined through their ability to reconcile text with the relationship between the viewer and the physicality of objects that are communicating these histories.

As family heirlooms are packed into trunks and moved to new locations, they begin to simultaneously operate in both locational narratives, amongst those who both own the items and feel emotional claim (or connection) to them. This method of describing yourself through these objects and their histories is at the core of my work, and of my Degree Project.